Click to enlarge

THE O'DEA'S IN COUNTY CLARE

There is strong evidence, including DNA evidence, that the O'Dea family originated in County Clare and emigrated to County Limerick sometime in the 18th century. The following is an article written by Dave Lewis titled "ROOTS: The Rebel O'Dea's" which appeared on the Irish History magazine for August / September 2017 and was reproduced on its website.

In the past and at present alike, the name O’Dea is almost exclusively associated with the County Clare and adjacent areas such as Limerick City and north Tipperary. Though it is not a common name elsewhere, and even within County Clare is uncommon outside of the part of the county where it originated, it is an ancient and noble name with associations ranging from battle prowess to religion and science.

The name, also spelled O’Day, O’Dee, and occasionally Daw, originates from the 10th century chieftain of the clan Déaghaidh, who came to rule much of southwest Clare, bordered by the Fergus river to the east, the Burren to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the Shannon estuary to the south. The family claims that Déaghaidh, anglicized as Dea, is one of the first surnames that appeared in Europe. While the Ó Deághaidh’s had lordship over this area, they were déis, vassals, under the Dál gCais, a powerful 10th century dynasty. Déaghaidh is referenced later in Geoffrey Keating’s Foras Feasa ar Éireann, known in English simply as the “History of Ireland,” as one of 500 men who aided Brian Boru’s father in rescuing the King of Munster from a Viking ship.

Around 400 years after this rescue, the O’Dea’s played another vital military role in the defense of Gaelic owned land and lordship against a different foreign invader, the Normans.

The Battle of Dysert O’Dea took place on the 10th of May 1318. It was loosely part of Scottish king Robert the Bruce’s campaign in Ireland, during which he sent his brother, Edward, to Ireland, hoping to unite the Scots militarily with the Gaelic lords against the Hiberno-Norman lords, effectively opening a second front in his war against the English crown. As a result, a number of proxy battles occurred during this time between the Normans and the Gaels, only occasionally having a direct relationship to the Bruce campaign.

The battle began when the Norman Richard de Clare, a descendent of Strongbow, attacked the Gaelic Kingdom of Thomond, an area of Clare which had long resisted foreign control, hoping to install a Norman sympathizer as king. De Clare had over 800 knights and foot soldiers who marched on Dysert O’Dea, the stronghold of the Ó Deághaidh clan, thinking they had the upper hand over the Gaels. Clan chief Conchobar Ó Deághaidh, renowned as a brilliant tactician, feigned retreat, causing de Clare to order a charge on the open Irish, hoping for a decisive blow. Instead, Ó Deághaidh’s troops surrounded the Norman party, resulting in Richard de Clare’s death by Conchobar Ó Deághaidh’s own axe as well as the death of de Clare’s son. When de Clare’s wife learned this, she torched their family castle and estate before fleeing to England. The battle was a decisive blow and the Kingdom of Thomond would not be controlled or influenced by a foreign ruler for another 200 years.

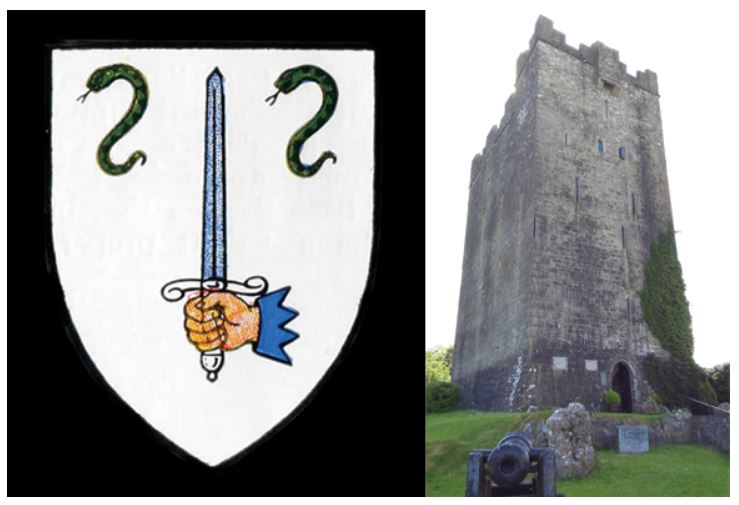

It was in these years that the most enduring symbol of the O’Dea clan was built in the area – a fortified tower known as O’Dea Castle, completed in the 1490s. The tower was lost and regained by the O’Deas throughout the 16th and 17th centuries and was even used as a stronghold by Cromwellian forces. It was eventually was seized by the Synge family, landlords during the 19th century. In 1970, the castle returned to O’Dea hands, when John O’Day, an Irish American from Wisconsin, purchased the building and had it restored. Since 1986, O’Dea Castle has been open to the public, serving as the Clare Archeology Centre.

The land over which the Ó Deághaidh’s ruled also had a role in the early days of Christianity in Ireland. Saint Tola established a monastery and built a round tower on the land in the eighth century, and a high cross that housed a relic of Saint Tola was erected later in the 11th century. This influence must have made an impact on the O’Dea clan, as various members have risen to the office of bishop.

The first of these was Cornelius O’Dea (d. 1434), who was appointed as Bishop of Limerick in 1400, only 82 year after the triumphant battle of Dysert O’Dea. Three artifacts survive from his time as bishop – his crozier, a manuscript called the Black Book of Limerick, and his mitre. According to legend, Bishop O’Dea forgot his own mitre and crozier when he traveled to Dublin for an important synod with the other bishops of Ireland. Feeling awkward, the bishop scoured the city unsuccessfully for replacements until a young boy presented the him with a box, saying only that it contained what he sought and if the bishop was pleased he could keep it. O’Dea opened the box and, seeing what was inside, turned to thank the boy, but he was nowhere to be seen. The crozier and mitre can still be seen today as they are housed in Limerick’s Hunt Museum and the crozier has been used on solemn occasions by subsequent Bishops of Limerick.

The next Bishop O’Dea was Thomas O’Dea (1858 – 1923), who held two bishoprics, Galway and Clonfert. In 1903, Thomas was named as Bishop of Clonfert and, six years later, named Bishop of Galway. During his time as bishop, he planned to build a new cathedral for Clonfert but these plans were interrupted by the arrival of the First World War. He was a Gaeilgeoir and was an ardent supporter of the GAA.

The third Bishop O’Dea, Edward John O’Dea (1856 – 1932), was appointed bishop of the Seattle diocese in 1896 (it was called the Diocese of Nesqually until 1907) and served until his death in 1932. During his time in Seattle, the O’Dea dealt with financial difficulties, guiding his flock during the First World War, and a threat from the Ku Klux Klan that tried to make parochial schools illegal. He late went on to establish Saint Edward’s Seminary school in Kenmore, Washington, and O’Dea High School in Seattle in 1923.